WHO INHERITS KEMET? CULTURAL AMNESIA, PHARAOHISM, AND THE AFRICAN CLAIM TO ANCIENT EGYPT

WHO INHERITS KEMET? CULTURAL AMNESIA, PHARAOHISM, AND THE AFRICAN CLAIM TO ANCIENT EGYPT

The ruins of ancient Kemet, commonly known as “Ancient Egypt, are not only symbols of a powerful past but also sites of contested ownership. Everyone wants a piece of Egypt’s grandeur—Arabized Egyptians, Europeans, Christian Copts, and even global media companies all have staked a claim. However, beneath the tourist spectacles and mythmaking lies an uncomfortable question: Who truly inherits Kemet’s legacy?

The truth? Most people claiming that inheritance today are cosplaying.

Let’s begin with the modern Egyptian state. Today’s identity in Egypt is predominantly Arab and Islamic, a result of the 7th-century Arab conquest. Prior to this, Kemet had already experienced multiple foreign conquests, by the Persians, Greeks, and Romans. By the time Napoleon’s French scholars arrived in Egypt in 1798, Egypt’s original cultural identity had been severely disrupted. The knowledge of Medu Neter (the sacred Kemetian language) had been lost to the general population. As historian Sally-Ann Ashton explains, “The real continuity of Egyptian culture was interrupted by the Greek and Roman conquests, and later by the Arab invasion in the seventh century” (Ashton, Egypt’s Place in the Ancient World). By this point, the Egyptian people had little connection to the civilization that once flourished on the banks of the Nile.

This is where Pharaohism enters the picture.

Pharaohism is a nationalist ideology in which the modern Egyptian state lays claim to the grandeur of the pharaonic past, often to bolster its own legitimacy. In this narrative, Egypt’s Arabized identity is directly linked to the glory of ancient Kemet. However, Pharaohism is not cultural continuity; it is state-driven cosplay, a selective appropriation of Kemetian symbols for political gain. The use of pharaonic imagery in modern Egyptian nationalism has little to do with cultural preservation and more to do with constructing a national identity. Professor Shomarka Keita, a leading anthropologist, argues, “Pharaohism is a political identity constructed for the modern Egyptian state, one that seeks to minimize or even erase the African roots of ancient Kemet” (Keita, Cultural Identities and Historical Legacy).

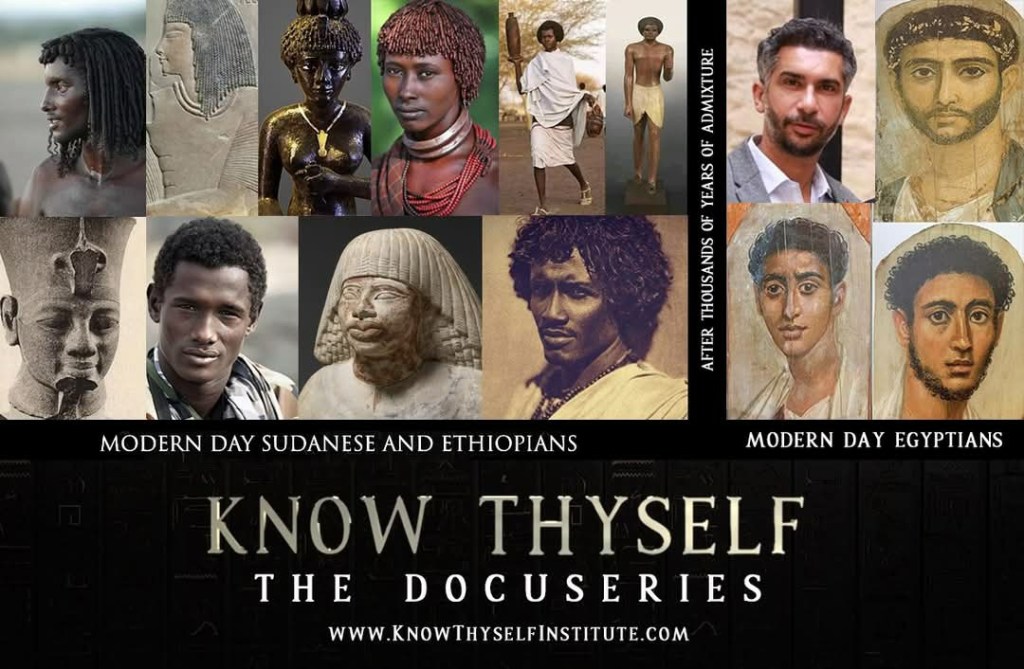

Yet ironically, many Egyptians, particularly in Upper Egypt, carry ancient African haplogroups and genetic connections to the Kemetyu. Their features alone often testify to this ancestry, revealing phenotypes consistent with African heritage or clear evidence of mixed ancestry. This is not speculative, it’s observable. Volney saw it as the “true solution to the enigma (of how the modern Egyptians came to have their ‘mulatto’ appearance).” He postulated that the Copts were “true negroes” of the same stock as all the autochthonous peoples of Africa, and that they “after some centuries of mixing…, must have lost the full blackness of its original color” (Mokhtar, General History of Africa II).

But not everyone agreed on the extent of continuity. In 1839, Jean-François Champollion, the father of Egyptology, pointedly stated: “In the Copts of Egypt, we do not find any of the characteristic features of the ancient Kemetian population. The Copts are the result of crossbreeding with all the nations that successfully dominated Kemet. It is wrong to seek in them the principal features of the old race” (Champollion-Figeac, Égypte ancienne, 1839). This underscores a fundamental contradiction: the biological remnants of Kemet may survive, but their cultural and ideological inheritance has been diluted or, in many cases, erased.

Some modern Egyptians have completely disengaged from the controversy, living outside the historical debate altogether. Others, however, have fully adopted colonial narratives, distancing themselves from their African lineage in favor of an Arab or Mediterranean identity. This contradiction is rarely acknowledged: a person can both whitewash history and have partial lineage to it at the same time. The two are not mutually exclusive. Biological inheritance does not equate to cultural stewardship, especially when historical amnesia is the prevailing mindset.

Then there is the Coptic Church, often seen as the “true heir” of ancient Egypt. The Copts, as Egypt’s indigenous Christian community, claim cultural continuity with the pharaonic past through their language, Coptic, which is the last known stage of the ancient Egyptian language. Some scholars, like Sally-Ann Ashton, argue that the Copts are indeed the heirs of ancient Kemet, preserving some elements of the ancient Kemetian worldview.

However, the Coptic claim is not without its issues. Coptic identity is, in reality, a product of Greco-Roman and Christian influences. While the Copts certainly retained aspects of Kemetic culture, primarily linguistic connections to the ancient Medu Neter, the primary foundation of their identity was shaped under Hellenistic and Roman rule. Christianity, the dominant religion of the Coptic community, was introduced to Kemet through Roman colonialism, and its ideology, ritual, and symbols have little to do with the original religious worldview of the ancient Kemetyu. The “Egyptian” identity is a product of colonialism and the erasure of the Kemetyu represents that erasure.

As Ashton notes, “While Coptic Christianity preserves some elements of Egyptian religious thought, it is largely a product of the Hellenistic and Roman cultural influence that shaped Egypt after the conquest of Alexander the Great” (Ashton, Egypt’s Place in the Ancient World). The Copts preserved fragments of ancient Egyptian symbolism, but they did not maintain the Kemetic worldview. Thus, the Copts’ claim to the legacy of Kemet is tenuous at best. It represents a hybridized, post-Kemet identity, shaped by multiple layers of foreign influence.

So, who inherits Kemet? Not the Arabs, not the Copts, and certainly not the colonial powers that “rediscovered” Kemet in the 19th century. The true heirs of Kemet are the broader African world—the people who, despite colonialism, have maintained living continuities with ancient Kemet:

- Cattle culture, sacred in Kemet, remains central to many Nilotic peoples, including the Dinka and Maasai, where cattle are revered not just as livestock but as divine symbols. Kenyans , Sudanese and and Ugandans still to this day have the harmonious relationship with the Ankole Cattle, the same cattle herded by the ancient Kemetyu.

- Ethno-trichology, or the cultural significance of hair, continues to thrive among African communities, from Fulani and Massaai braids to the locs of the rural Ethiopians, reflecting the same emphasis on hair as a signifier of identity that was prominent in ancient Kemet.

- Language remains a key connection: Medu Neter (ancient Egyptian) shares linguistic features with languages like Amharic, Oromo, and Tigrinya, which are still spoken across the Horn of Africa and the Nile Valley. As Christopher Ehret states, “The Afroasiatic family of languages, to which both ancient Kemet and many modern African languages belong, provides a crucial link between ancient Kemet and its African neighbors” (Ehret, History and the Languages of Africa).

- Spiritual systems rooted in Ma’at—balance, truth, order, survive in African societies such as the Akan of the Asante Empire and Edo of Benin, reflecting the same ethical and cosmic laws articulated in Kemet. As Shomarka Keita points out, “The cosmologies and spiritual practices of many African peoples carry echoes of the ethical and cosmic principles that first took shape in Kemet” (Keita, Cultural Identities and Historical Legacy).

This is not a nostalgic search for the past; it is living continuity. Kemet never truly vanished, it migrated, adapted, and survived in the practices, language, and worldviews of African peoples. And let’s be clear: the rush to claim Kemet as Arab, Mediterranean, or Coptic is not a neutral gesture. It is a political erasure of Africa’s central role in human history. As Professor Keita emphasizes, “The marginalization of African identity in the modern narrative of Kemet is a form of cultural appropriation, which seeks to sever the African connection to the civilization that defined much of human progress” (Keita, Cultural Identities and Historical Legacy).

Egyptian born Egyptologist, Professor Fekri Hassan expresses this sentiment beautifully:

Egypt is situated where African cultural developments conjoin, mingle, and blend with those of neighboring cultures of southwest Asia and the Mediterranean. Yet, Egyptology, through its Euro-centered perspectives, has generally been lax in exploring and valorizing Egypt’s African origins.

This not only leads to theoretical shortcomings but also to serious ethical ramifications undermining efforts for a new world of justice, equity, and fraternity….Egyptologists need to engage in emphasizing the grounding of Egypt in African cultures and its interaction throughout its history with African cultures. This would be a first step in reconsidering the sociopolitical biases that not only isolate modern Egypt from its ancient past, but also reorient Egyptology to deal with intercultural dynamics…”

Dr. Hassan received his B.S. and M.S. degrees from Ain Shams University and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Southern Methodist University. Source: http://www.nilevalleycollective.com

Just as Europe has adopted Ancient Greece as its classical civilization, proudly claiming it as the foundation of Western thought, Africa has inherited Kemet as its own. This is not simply a matter of cultural pride; it is a rightful claim. Just as Europeans embrace the classical ideals of Athens and Sparta, African peoples claim the achievements, knowledge, and philosophy of Kemet as their own. Kemet belongs to Africa—not as a distant, disconnected civilization, but as a foundational part of African identity and heritage.

So who inherits Kemet? It’s not those who live on the land today but have divorced themselves from their African roots. It’s not those who market Kemet as a tourist attraction or use it for political purposes while they desecrate the graves of those they claim and put them on display for profit. It is those who still live by its worldview, principles, and spiritual practices. Kemet is not a brand. It is not a trophy. It is not a backdrop. It is a memory kept alive in Africa’s bones, breath, and blood. Let the Pharaohists keep the monuments. Let the tourists take their pictures. The memory belongs to the people.

- • •

References:

Ashton, S.-A. (2011). Egypt’s Place in the Ancient World: The Coptic Identity and Egypt’s Transformation. University Press.

Budge, E. A. W. (1991). Quoted in Diop, C. A. Civilization or Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology (Foreword, pp. 1–10). Brooklyn, NY: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN: 978-1-55652-048-8.

Champollion-Figeac, J. J. (1839). Égypte ancienne. Paris: Firmin Didot Frères.

Diop, C. A. (1991). Civilization or Barbarism: An Authentic Anthropology. Brooklyn, NY: Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN: 978-1-55652-048-8.

Ehret, C. (2002). History and the Languages of Africa. University of California Press. ISBN: 978-0-520-22929-7.

Keita, S. O. Y. (2002). Cultural Identities and Historical Legacy: African Continuities in Ancient Egypt. African Studies Journal.

Mokhtar, G. (Ed.). (1990). General History of Africa II: Ancient Civilizations of Africa (pp. 1–118). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN: 978-0-520-06697-7.

Volney, C.-F. (1791). Travels in Egypt and Syria

- • •

Visit our official website for Merch:

https://www.knowthyselfinstitute.com/shop

The Origins of Egyptology | WATCH NOW:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O0N_hrDzFy0&t=653s

“I have not spoken angrily or arrogantly. I have not cursed anyone in thought, word or deeds.” ~ 35th & 36th Principals of Ma’at