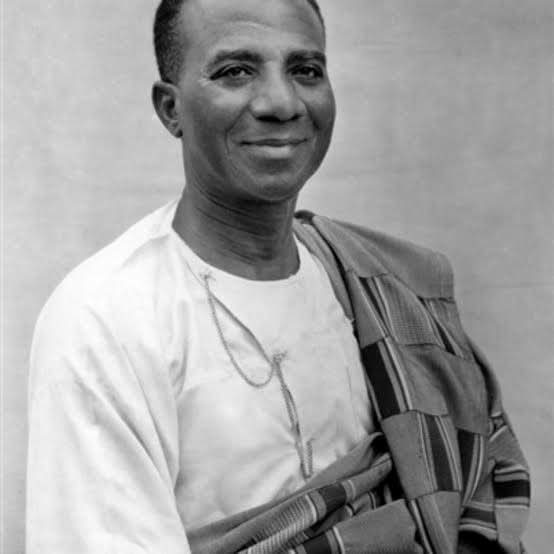

Sylvanus Olympio (6 September 1902 – 13 January 1963) was a pivotal figure in Togo’s history,

Sylvanus Olympio (6 September 1902 – 13 January 1963) was a pivotal figure in Togo’s history, serving as the country’s first prime minister (1958–1961) and first president (1961–1963) after leading the charge for independence from French colonial rule. His story is one of ambition, vision, and tragedy, shaped by his unique background and the turbulent politics of post-colonial Africa.

Born in Kpandu, in what was then the German protectorate of Togoland (now part of Ghana), Olympio came from a wealthy Afro-Brazilian family. His grandfather, Francisco Olympio Sylvio, was a prominent Brazilian trader, and his father, Epiphanio, ran a successful trading house in Agoué (present-day Benin). His uncle, Octaviano Olympio, was one of Togo’s richest men, cementing the family’s elite status within a mixed Brazilian and African aristocratic community. This cosmopolitan heritage gave Olympio a unique perspective, bridging African and Western worlds.

Olympio’s education reflected his privileged background. He studied at a German Catholic school in Lomé, built by his uncle, and later at British schools after the 1914 Anglo-French conquest of Togoland. He went on to earn a commerce degree from the London School of Economics in 1925, studying under notable figures like Harold Laski. His academic prowess and multilingual fluency (German, English, French, Portuguese, and Yoruba) set him apart. After graduating, he joined Unilever, rising to general manager of the United Africa Company’s African operations by 1938.

World War II marked a turning point. The Vichy French authorities, suspecting his British ties, arrested him in 1942 and held him under surveillance in Djougou, French Dahomey. This experience soured his view of French colonial rule, pushing him toward the independence movement. Post-war, he became a leading voice for Togolese independence, leveraging Togo’s status as a UN trust territory to petition the United Nations Trusteeship Council in 1947—the first such petition for grievance resolution. As head of the Comité de l’Unité Togolaise (CUT), he also championed the reunification of the Ewe people, split across Togo, Ghana, and Benin due to colonial borders. However, this cause faltered due to opposition from Britain, France, and Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah.

Olympio’s political ascent was rapid but fraught. His CUT boycotted elections in the 1950s due to French interference, and in 1954, French authorities briefly stripped him of his voting and candidacy rights on dubious charges of currency trafficking. Yet, in 1958, UN-supervised elections saw CUT win overwhelmingly, making Olympio prime minister. He led Togo to full independence on 27 April 1960 and became president in 1961 after winning over 90% of the vote in a single-party election, with a constitution granting him extensive powers.

His presidency was marked by pragmatism and caution. Togo, small and resource-poor, faced economic challenges, exacerbated by Nkrumah’s border closure with Ghana. Olympio maintained ties with Western powers like Britain and the United States—meeting President John F. Kennedy in 1962—while distancing Togo from the French Community and later the Organisation of African Unity. His strict financial management, including repaying debts to France, and his refusal to expand Togo’s small army (to avoid unnecessary costs) created domestic tensions. Returning Togolese veterans from French wars in Indochina and Algeria, denied integration into the army, grew resentful, and northern leaders felt excluded from his southern-dominated government.

Olympio’s most audacious move was his plan to exit the CFA franc zone and create a Togolese currency backed by the German Deutsche Mark. This alarmed France, particularly Jacques Foccart, de Gaulle’s key advisor on African affairs, who viewed Olympio as unreliable compared to his pro-French rival, Nicolas Grunitzky (Olympio’s brother-in-law through his wife, Dina Grunitzky).

On the night of 12 January 1963, a military coup led by disgruntled ex-soldiers, including Étienne (later Gnassingbé) Eyadéma, attacked Olympio’s residence in Lomé. With only two guards, Olympio escaped over the garden wall into the U.S. embassy compound, hiding in a parked car. At around 7:15 a.m. on 13 January, he was found and shot dead near the embassy gate. Eyadéma later claimed responsibility, though a 2011 statement by a Togolese officer suggested a French soldier, “PAUC,” fired the fatal shots. The exact role of France and the U.S. remains murky, with declassified documents scarce and both nations reticent.

The coup, the first in post-colonial Africa, installed Grunitzky as president, but Eyadéma seized power in 1967, ruling until 2005. His son, Faure Gnassingbé, remains Togo’s president, perpetuating a vendetta with Olympio’s family, notably his son Gilchrist, who survived an assassination attempt in 1992. Olympio’s vision of a sovereign, self-determining Togo, free from French influence, made him a target. His assassination, widely mourned across Africa, marked a grim precedent for the military coups that plagued the continent in the 1960s.

Olympio’s legacy endures as a symbol of African liberation and resistance to neocolonialism. Posts on X reflect ongoing sentiment in Togo, with some calling him a visionary martyr killed for defying France, while others note the complexity of his authoritarian rule. His dream of Ewe reunification and economic independence remains unfulfilled, but his role as Togo’s “father of independence” cements his place in history.