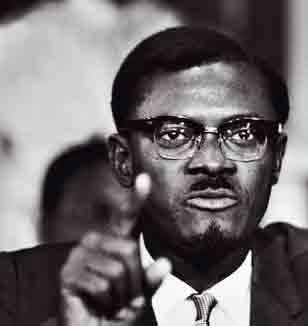

Had he not been assassinated by the CIA, Patrice Lumumba would have been 100 years old today…

Had he not been assassinated by the CIA, Patrice Lumumba would have been 100 years old today…

Patrice Lumumba was an Afrikan revolutionary, politician and independence leader who served as the first Prime Minister of the independent Democratic Republic of the Congo (then Republic of the Congo).

Patrice Lumumba, in full Patrice Hemery Lumumba, (born July 2, 1925, Onalua, Belgian Congo [now the Democratic Republic of the Congo]—died January 1961, Katanga province), African nationalist leader, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (June–September 1960). Forced out of office during a political crisis, he was assassinated a short time later.

Lumumba was born in the village of Onalua in Kasai province, Belgian Congo. He was a member of the small Batetela ethnic group, a fact that became significant in his later political life. His two principal rivals, Moise Tshombe, who led the breakaway of the Katanga province, and Joseph Kasavubu, who later became the Congo’s president, both came from large, powerful ethnic groups from which they derived their major support, giving their political movements a regional character. In contrast, Lumumba’s movement emphasized its all-Congolese nature.

After attending a Protestant mission school, Lumumba went to work in Kindu-Port-Empain, where he became active in the club of the évolués (Western-educated Africans). He began to write essays and poems for Congolese journals. He also applied for and received full Belgian citizenship. Lumumba next moved to Léopoldville (now Kinshasa) to become a postal clerk and went on to become an accountant in the post office in Stanleyville (now Kisangani). There he continued to contribute to the Congolese press.

In 1955 Lumumba became regional president of a purely Congolese trade union of government employees that was not affiliated, as were other unions, to either of the two Belgian trade-union federations (socialist and Roman Catholic). He also became active in the Belgian Liberal Party in the Congo. Although conservative in many ways, the party was not linked to either of the trade-union federations, which were hostile to it. In 1956 Lumumba was invited with others on a study tour of Belgium under the auspices of the minister of colonies. On his return he was arrested on a charge of embezzlement from the post office. He was convicted and condemned one year later, after various reductions of sentence, to 12 months’ imprisonment and a fine.

Get unlimited ad-free access to all Britannica’s trusted content.

When Lumumba got out of prison, he grew even more active in politics. In October 1958 he, along with other Congolese leaders, launched the Congolese National Movement (Mouvement National Congolais; MNC), the first nationwide Congolese political party. In December he attended the first All-African People’s Conference in Accra, Ghana, where he met nationalists from across the African continent and was made a member of the permanent organization set up by the conference. His outlook and vocabulary, inspired by pan-African goals, now took on the tenor of militant nationalism.

As nationalist fervour increased, the Belgian government announced a program intended to lead to independence for the Congo, starting with local elections in December 1959. The nationalists regarded this program as a scheme to install puppets before independence and announced a boycott of the elections. The Belgian authorities responded with repression. On October 30 there was a clash in Stanleyville that resulted in 30 deaths. Lumumba was imprisoned on a charge of inciting to riot.

The MNC decided to shift tactics, entered the elections, and won a sweeping victory in Stanleyville (90 percent of the votes). In January 1960 the Belgian government convened a Round Table Conference in Brussels of all Congolese parties to discuss political change, but the MNC refused to participate without Lumumba. Lumumba was thereupon released from prison and flown to Brussels. The conference agreed on a date for independence, June 30, with national elections in May. Although there was a multiplicity of parties, the MNC came out far ahead in the elections, and Lumumba emerged as the leading nationalist politician of the Congo. Maneuvers to prevent his assumption of authority failed, and he was asked to form the first government, which he did on June 23, 1960.

A few days after independence, some units of the army rebelled, largely because of objections to their Belgian commander. Moise Tshombe took advantage of the ensuing confusion, using it as an opportunity to proclaim that the mineral-rich province of Katanga was seceding from the Congo. Belgium sent in troops, ostensibly to protect Belgian nationals in the disorder, but the Belgian troops landed principally in Katanga, where they sustained Tshombe’s secessionist regime.

The Congo appealed to the United Nations to expel the Belgians and help them restore internal order. As prime minister, Lumumba did what little he could to redress the situation. His army was an uncertain instrument of power, his civilian administration untrained and untried; the United Nations forces (whose presence he had requested) were condescending and assertive, and the political alliances underlying his regime very shaky. The Belgian troops did not leave, and the Katanga secession continued.

Since the United Nations forces refused to help suppress the Katangese revolt, Lumumba appealed to the Soviet Union for planes to assist in transporting his troops to Katanga. He asked the independent African states to meet in Léopoldville in August to unite their efforts behind him. His moves alarmed many, particularly the Western powers and the supporters of President Kasavubu, who pursued a moderate course in the coalition government and favoured some local autonomy in the provinces.

On September 5 President Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba, but the legalities of the move were immediately contested by Lumumba; as a result of the discord, there were two groups now claiming to be the legal central government. On September 14 power was seized by the Congolese army leader Colonel Joseph Mobutu (later president of Zaire as Mobutu Sese Seko), who later reached a working agreement with Kasavubu. In October the General Assembly of the United Nations recognized the credentials of Kasavubu’s government. The independent African states split sharply over the issue.

In November Lumumba sought to travel from Léopoldville, where the United Nations had provided him with protection, to Stanleyville, where his supporters had control. He was caught by the Kasavubu forces and arrested on December 2. On January 17, 1961, he was delivered to the secessionist regime in Katanga, where he was murdered. His death caused a scandal throughout Africa; retrospectively, even his enemies proclaimed him a “national hero.”

Foreign involvement in his death

Both Belgium and the US were influenced by the Cold War in their positions toward Lumumba, as they feared communist influence. They thought he seemed to gravitate toward the Soviet Union, although according to Sean Kelly, who covered the events as a correspondent for the Voice of America, this was not because Lumumba was a communist, but because the USSR was the only place he could find support for his country’s effort to rid itself of colonial rule. The US was the first country from which Lumumba requested help. Lumumba, for his part, denied being a communist, and said that he found colonialism and communism to be equally deplorable. He professed his personal preference for neutrality between the East and West.

Belgian involvement

On 18 January, panicked by reports that the burial of the three bodies had been observed, members of the execution team went to dig up the remains and move them for reburial to a place near the border with Northern Rhodesia. Belgian Police Commissioner Gerard Soete later admitted in several accounts that he and his brother led the original exhumation. Police Commissioner Frans Verscheure also took part. On the afternoon and evening of 21 January, Commissioner Soete and his brother dug up Lumumba’s corpse for a second time, cut it up with a hacksaw, and dissolved it in concentrated sulfuric acid.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, Lumumba’s assassination was investigated. In a 1999 interview on Belgian television in a program about his assassination, Soete displayed a bullet and two teeth that he claimed he had saved from Lumumba’s body. According to the 2001 Belgian Commission investigating Lumumba’s assassination: Belgium wanted Lumumba arrested, Belgium was not particularly concerned with Lumumba’s physical well being, and although informed of the danger to Lumumba’s life, Belgium did not take any action to avert his death. The report concluded that Belgium had not ordered Lumumba’s assassination. In February 2002, the Belgian government formally apologized to the Congolese people, and admitted to a “moral responsibility” and “an irrefutable portion of responsibility in the events that led to the death of Lumumba”.

Lumumba’s execution was carried out by a firing squad led by Belgian Captain Julien Gat; another Belgian, Police Commissioner Verscheure, had overall command of the execution site.

In the early 21st century, writer Ludo De Witte found written orders from the Belgian government that had requested Lumumba’s execution and documents on various arrangements, such as death squads. He published a book in 2003 about the assassination of Lumumba.

United States involvement

The 2001 report by the Belgian Commission describes previous U.S. and Belgian plots to kill Lumumba. Among them was a Central Intelligence Agency-sponsored attempt to poison him, which was ordered by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. CIA chemist Sidney Gottlieb, a key person in this plan, devised a poison resembling toothpaste. In September 1960, Gottlieb brought a vial of the poison to the Congo with plans to place it on Lumumba’s toothbrush. This plot was abandoned, allegedly because Larry Devlin, CIA Station Chief for the Congo, refused permission.

As Kalb points out in her book, Congo Cables, the record shows that many communications by Devlin at the time urged elimination of Lumumba. Also, the CIA station chief helped to direct the search to capture Lumumba for transfer to his enemies in Katanga. Devlin was involved in arranging Lumumba’s transfer to Katanga; and the CIA base chief in Elizabethville was in direct touch with the killers the night Lumumba was killed. John Stockwell wrote in 1978 that a CIA agent had the body in the trunk of his car in order to try to get rid of it. Stockwell, who knew Devlin well, believed that Devlin knew more than anyone else about the murder.

The inauguration of John F. Kennedy in January 1961 caused fear among Mobutu’s faction and within the CIA that the incoming Democratic administration would favor the imprisoned Lumumba. While awaiting his presidential inauguration, Kennedy had come to believe that Lumumba should be released from custody, though not be allowed to return to power. Lumumba was killed three days before Kennedy’s inauguration on 20 January, though Kennedy would not learn of the killing until 13 February.

Church Committee

In 1975, the Church Committee went on record with the finding that CIA chief Allen Dulles had ordered Lumumba’s assassination as “an urgent and prime objective”.

Furthermore, declassified CIA cables quoted or mentioned in the Church report and in Kalb (1982) mention two specific CIA plots to murder Lumumba: the poison plot and a shooting plot.

The Committee later found that while the CIA had conspired to kill Lumumba, it was not directly involved in the murder.

U.S. government documents

In the early 21st century, declassified documents revealed that the CIA had plotted to assassinate Lumumba. These documents indicate that the Congolese leaders who killed Lumumba, including Mobutu Sese Seko and Joseph Kasa-Vubu, received money and weapons directly from the CIA. This same disclosure showed that at that time, the U.S. government believed that Lumumba was a communist and feared him because of what it considered the threat of the Soviet Union in the Cold War.

In 2000, a newly declassified interview with Robert Johnson, who was the minutekeeper of the U.S. National Security Council at the time in question, revealed that U.S. President Eisenhower had said “something [to CIA chief Allen Dulles] to the effect that Lumumba should be eliminated.” The interview from the Senate Intelligence Committee’s inquiry on covert action was released in August 2000.

In 2013, the U.S. State Department admitted that President Eisenhower authorized the murder of Lumumba. However, documents released in 2017 revealed that an American role in Lumumba’s murder was only under consideration by the CIA. CIA Chief Allan Dulles had allocated $100,000 to accomplish the act, but the plan was not carried out.

British involvement

In April 2013, in a letter to the London Review of Books, British parliamentarian David Lea reported having discussed Lumumba’s death with MI6 officer Daphne Park shortly before she died in March 2010. Park had been posted to Leopoldville at the time of Lumumba’s death, and was later a semi-official spokesperson for MI6 in the House of Lords. According to Lea, when he mentioned “the uproar” surrounding Lumumba’s abduction and murder, and recalled the theory that MI6 might have had “something to do with it”, Park replied, “We did. I organised it.” BBC reported that, subsequently, “Whitehall sources” described the claims of MI6 involvement as “speculative”.