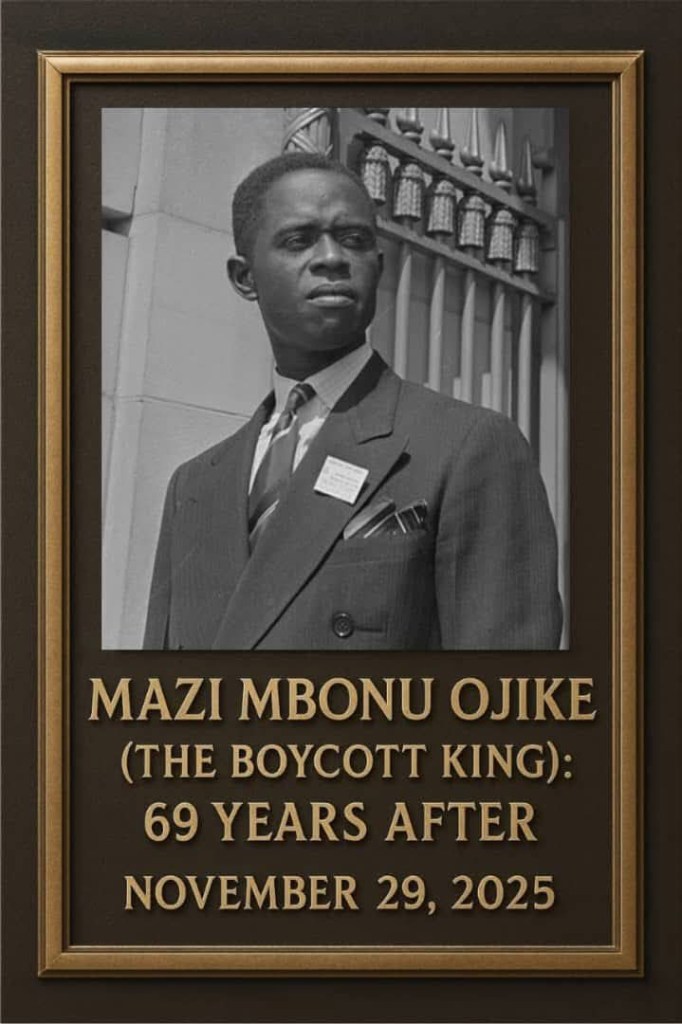

MAZI MBONU OJIKE: REMEMBERING THE BOYCOTT KING 69 YEARS AFTER

MAZI MBONU OJIKE: REMEMBERING THE BOYCOTT KING 69 YEARS AFTER

On November 29, 1956, in a hospital ward in Enugu, a brief but blazing life came to an abrupt end. The man who died that day was only 42, but he had already etched his name in the annals of Nigerian history as the Boycott King, the Freedom Choirmaster, and the Cultural Evangelist. His name was Mazi Mbonu Ojike – a teacher, journalist, pan-Africanist, politician and one of the most original minds of the nationalist generation. Sixty-nine years after his passing, the story of his life remains evergreen, poignant and a fascinating chronicle of selflessness, uncommon focus and commitment.

Mbonu Ojike was born in 1914 at Ndiakeme Uno, Arondizuogu, in present-day Ideato North LGA, Imo State, into the large polygamous household of Mazi Ojike Emeanulu. Mbonu’s mother was Mgbeke. His father was a prosperous Aro trader, and like many traders of his generation he preferred his sons to follow his footsteps rather than waste time in school. Young Mbonu thought otherwise. Defying family expectations, he insisted on formal education and enrolled at CMS School, Arondizuogu, where he distinguished himself as a bright and serious pupil. By 1925 he was already a pupil-teacher at the Anglican Central School in Arondizuogu and, later, at Abagana, teaching during the day while studying advanced lessons at night.

In 1929, he gained admission into the prestigious CMS Teachers’ Training College, Awka, graduating in 1931 with a Higher Elementary Teacher’s Certificate. There, he won the college prize associated with the famous book “Aggrey of Africa”, an experience that sharpened his awareness of the African predicament under colonial rule. Shortly afterwards he joined the staff of Dennis Memorial Grammar School (DMGS), Onitsha, one of the leading secondary schools in Eastern Nigeria. At DMGS he served as choirmaster, Sunday school supervisor and organist. These roles would later bolster his flair for music and performance at political rallies. But he also became restless. Disturbed by discrimination against African junior teachers, he led an agitation in 1936 for salary justice, accusing the authorities of unfairly raising only senior staff salaries. It was an early sign of his refusal to accept inequality quietly.

Gradually, young Mbonu grew disillusioned with a missionary education system he felt did not serve African development and suppressed African culture. He resigned from DMGS and worked briefly for West African Pilot in Lagos, where he came under the influence of the paper’s publisher, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe (Zik). Inspired by the writings and example of Zik and other African thinkers, Ojike decided to seek higher education abroad. In November 1938, he left the shores of Nigeria for the United States with other young men – part of the group that his kinsman and ally, Dr. K. O. Mbadiwe later romanticised as the “Seven Argonauts”. Mbonu Ojike and K.O. Mbadiwe were among those seven young men who were inspired to sail to the United States on December 31, 1938 in search of the Golden Fleece: others were George Igbodebe Mbadiwe, Otuka Okala, Dr. Nnodu Okongwu, Engr. Nwankwo Chukwuemeka, and Dr. Okechukwu Ikejiani. They were later joined by Dr. Abyssinia Akweke Nwafor Orizu.

Young Mbonu’s first port of call in the United States was Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. Then he moved to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and later Ohio State University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in Economics. He also obtained a master’s degree in Education and Administration. America did not merely educate him, it enlarged his vision and mission. He quickly emerged as a student leader and cultural ambassador. Among other roles, he was President, African Students Union at Lincoln University, Co-founder and General Secretary, African Academy of Arts and Research, Co-founder, African Students Association of the United States and Canada with K. O. Mbadiwe and John Karefa-Smart, Member, American Council on African Education.

Through these platforms he lectured extensively on African culture, colonialism and racism, writing rejoinders to distorted portrayals of Africa and organising African dance festivals in major U.S. cities. One famous photograph shows him and his ally, K. O. Mbadiwe, in full African dress, standing beside US First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt at an African Dance Festival in New York – a striking image of African audacity and self-assertion. During this period he wrote three important books:

▪️Portrait of a Boy in Africa (1945)

▪️My Africa (1946)

▪️I Have Two Countries (1947)

In these works, he explained African customs to Western readers, challenged notions of African inferiority and called for a mutually respectful relationship between Africa and the West.

Mbonu Ojike returned to Nigeria in 1947, armed with degrees, ideas and an unshakeable belief in Africa’s future. He rejoined West African Pilot, rising to become the General Manager and launching two widely read columns: “Weekend Catechism” and “Something to Think About.” In these columns he became a nationalism catechist, explaining politics, culture and economics in a question-and-answer style that ordinary readers could grasp. He attacked racial discrimination, criticised colonial policy and, above all, preached psychological liberation from inferiority.

The defining feature of Ojike’s message was cultural nationalism. He believed in what he called “selective importation and imitation”: Africans could borrow useful aspects of foreign culture, but must preserve the core of their own values and identity by which he meant:

▪️African names in place of English ones,

▪️African attire in homes, offices and public ceremonies,

▪️African food and palm wine instead of imported gin and champagne,

▪️African music and dance, including the founding of an All-African Dance Association.

He championed his patriotic views tactically and from this cultural advocacy emerged the slogan that would make him famous which he encapsulated in the expression “Boycott all Boycottables.” By this he meant: avoid unnecessary foreign luxuries, invest in education, industry and productive ventures at home. The press promptly christened him “The Boycott King” and the name stuck.

After the Iva Valley massacre of striking coal miners at Enugu in 1949, Ojike wrote a fiery article calling for concerted resistance to colonial brutality. The piece was judged seditious: he was arrested, tried, convicted and fined £40. Undeterred, he helped form the National Emergency Committee, a short-lived but influential organisation that protested racial discrimination across the country.

In party politics, Mbonu Ojike found his natural stage. Working hard behind the scenes as one of Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe’s lieutenants, he defined concepts, created slogans, drafted manifestoes, and planned rallies. He was also a gifted public speaker and orator who drove political gatherings to a frenzy with his large repertoire of memorable songs which earned him the affectionate title “the Freedom Choirmaster”. As a prominent member of the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC), he became a star attraction at rallies. Leveraging on his experience as a choir boy, he introduced singing to political rallies. His “Freedom Song” turned political meetings into open-air choirs, his chants and call-and-response style electrified crowds. He also popularised a now-familiar greeting: “Nigeria – Kwenu!” to which crowds responded with thunderous enthusiasm. As a master of language and performance, he made nationalism feel like a shared festival of hope.

In 1951, he contested elections to the Legislative Council from Lagos on the NCNC platform and won, becoming Second National Vice-President of the party and later Deputy Mayor of Lagos at the age of 37. By 1953, Ojike had shifted his political base to the Eastern Region and was elected into the Eastern House of Assembly. In 1954, he became Minister of Works, moving later that same year to the powerful post of Minister of Finance in the Eastern Regional Government at a time that Dr. M.I. Okpara (who later became Premier) was serving as Minister without Portfolio and, later, Minister of Health in the same government. By his superior political ranking and closeness to Zik, Mazi Mbonu Ojike would have taken over from Zik as Premier of the Eastern Region but the lot fell on Okpara because of Ojike’s premature death.

As Minister of Works, he cut the image of what one legislative colleague described as “more workman than Minister.” He travelled extensively to inspect projects, sometimes walking village paths or releasing his official car for staff while he continued on foot or bicycle. Numerous link roads and rural water schemes in Eastern Nigeria date from this period of energetic fieldwork. As Minister of Finance, he displayed impressive command of economic policy. His first budget speech drew praise even from opposition figures. The respected leader, Professor Eyo Ita, hailed it as a model of realism and proof that an African minister could manage an entire regional economy with distinction.

Among his most enduring contributions were:

- Introduction and championing of the Pay-As-You-Earn (PAYE) system of income tax, which remains in use today,

- Support for the establishment of the Eastern Region Finance Corporation, and

- Vigorous backing of African Continental Bank (ACB) as a symbol of indigenous financial capacity.

Through these measures he hoped to anchor political independence on firm economic foundations.

Beyond his offices, Ojike cultivated a distinctive personal style. He often appeared in agbada, jumper or other traditional attire rather than the colonial two or three-piece suit. Civil servants followed his example and gradually won the right to wear “native dress” to work. At official receptions he served palm wine instead of imported whisky or champagne. He used the Aro title “Mazi” so consistently that it became a popular substitute for “Mr.” across much of Igboland. He married two wives and had five children.

In the mid-1950s, dark clouds began to gather over the Eastern Regional Government’s financial dealings. Public funds from marketing board reserves had been invested through the Eastern Region Finance Corporation in the African Continental Bank, a bank founded by the Premier, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe, and regarded by many nationalists as a symbol of economic self-assertion. Critics alleged a conflict of interest and misuse of public money. In 1956, amid growing controversy, the British authorities set up the Foster-Sutton Commission of Inquiry to investigate the relationship between the Eastern Government, the Finance Corporation and the bank. At the centre of the storm stood the Premier, Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe (who was the target of the inquisition) and his devoted Minister of Finance, Ojike. Faced with a soul-wrenching dilemma: to step into the line of fire himself or watch his leader – his mentor, hero and icon – consumed by a scandal that could destroy everything they had built together.

Under intense scrutiny, Ojike resigned as Minister of Finance. At the tribunal, he accepted responsibility for authorising major investments in the bank and defended them as necessary to save an indigenous institution from collapse and to secure economic freedom for the region. The Foster-Sutton Commission sat for about fifty days. Its final report, released in December 1956, criticised the Premier’s conduct but the report was issued after Ojike’s death. Those close to events recall the immense psychological strain on the young minister, whose sense of loyalty to his leader and commitment to African enterprise were both on trial.

On November 29, 1956, while the tribunal still loomed over public life, Mbonu Ojike died at Park Lane Hospital, Enugu. Rumours flew about the possible cause of his demise. Some accounts attributed his death to hypertension brought on by excessive stress. Others hinted darkly at poisoning or some oath of loyalty. None has been conclusively proved. He was buried the very next day in his compound at Ndiakeme Uno, Arondizuogu. It was a day of sadness in Arondizuogu, in the Eastern Region, in Nigeria and in Africa. At the graveside, his political leader and friend Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe reportedly lamented: “Africa kills its leaders… Africa has killed Mbonu Ojike.” Whether taken literally or figuratively, that sentence captured the feeling of a continent that had lost one of its brightest sons at the height of his powers. For Arondizuogu, it was a year of many tragedies: Mbonu Ojike was not the only promising young man that Arondizuogu lost to the nationalist struggle that year: Hon. Dixon K. Onwenu who was Chairman of NCNC in PH and Deputy Mayor of that city died in an automobile accident aged 40. Hon. F.O. Mbadiwe who was a member of the House of Representatives also died the same year.

Measured strictly in years, Mazi Mbonu Ojike’s life was short. Measured in impact, it was extraordinary. From the boy who defied his father to attend school to the student leader who addressed global conferences; from the DMGS choirmaster to the Freedom Choirmaster of NCNC rallies; from a rustic village in Arondizuogu to the corridors of power in Lagos and Enugu, Mbonu Ojike moved with a speed and intensity that seemed to outrun time itself. His unique style blended scholarship with showmanship, deep reading with street-level connection, cultural pride with administrative competence. He left behind books that still speak, policies still in operation, institutions that still carry traces of his hand, and a phrase -“Boycott the boycottables” – that remains an indelible part of Nigeria’s political vocabulary.

Sixty-nine years after he took his final bow, the story of Mazi Mbonu Ojike endures as one of the most compelling narratives of courage, creativity, and commitment in Nigeria’s long and unstable march to nationhood. Yet, apart from a hostel here and there, a few side streets that bear his name, a struggling community hospital built by friends and admirers, and an admirable sculpture of him erected by the Ikedi Ohakim administration at the fore court of Ahiajoku Convention Centre, Owerri which was inexplicably removed by the Rochas Okorocha administration, no national honour, institution or enduring monument honours this unforgettable patriot who gave everything – including his life – in the service of his people.

Curiously, even the Okigwe – Arondizuogu – Uga Road that leads to Ojike’s humble home in Ndiakeme Uno has been abandoned for years, surrendered to neglect, dilapidation and turned into the operational base of known and unknown gunmen. Is this how a nation ensures that “the labour of our heroes past shall never be in vain”? Someday, this injustice will be corrected. And when it happens, the spirit of Mazi Mbonu Ojike – who died young yet, sixty-nine years later, stands taller than many who lived twice his years – will finally receive the honour that history has always reserved for him.

(Mazi Uche Ohia, Ph.D., a lawyer, farmer, cultural advocate, public intellectual and a former Commissioner for Tourism, Culture and Creative Arts, Imo State (2021–2024), writes from Arondizuogu)