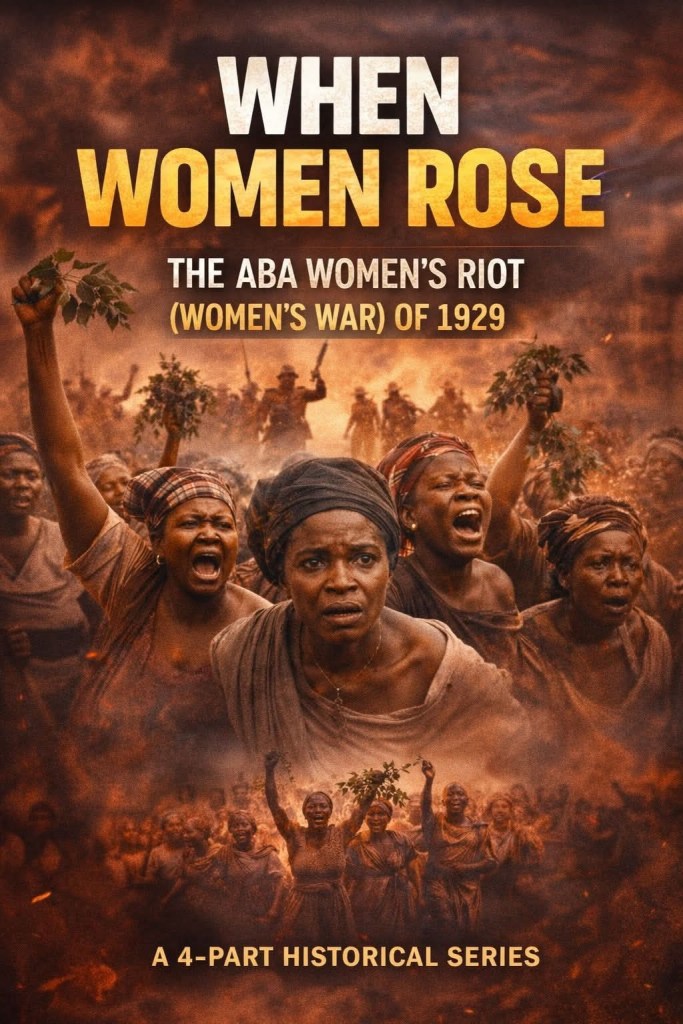

THE ABA WOMEN’S RIOT (WOMEN’S WAR) OF 1929

WHEN WOMEN ROSE

THE ABA WOMEN’S RIOT (WOMEN’S WAR) OF 1929

A 4-Part Historical Series

PART 1: BEFORE THE SHOUT — HOW SILENCE WAS FORCED ON WOMEN

Before the protest, before the songs, before the blood, there was silence.

Not the peaceful kind.

The dangerous kind.

In the villages and towns of Eastern Nigeria—Aba, Owerri, Calabar—women worked endlessly. They farmed the land, traded in the markets, raised children, cooked, cleaned, healed, and held communities together. Yet in the eyes of the British colonial government, they were invisible.

Colonial rule did not arrive gently.

It came with new laws, foreign authority, and men appointed as leaders over people who never chose them. These men were called warrant chiefs—local men empowered by the British to collect taxes, enforce rules, and control communities.

They answered upward, not outward.

And the first people they ignored were women.

Before colonialism, Igbo women had power structures. They had councils. They had voices in community decisions. They had economic authority through markets. When men abused power, women had a system of correction called “sitting on a man.”

It was collective discipline.

Women would gather at a man’s compound, sing mocking songs, dance, ridicule him publicly, and refuse to leave until he changed his ways. It was non-violent, but it was powerful. Shame was justice.

The British did not understand this system.

They dismantled it.

Under colonial rule, women were excluded from governance. Markets were controlled. Decisions were made without them. Taxes were imposed on men, and women were forced to pay indirectly—through labor, through levies, through survival.

Still, the women endured.

Until the rumour began to move like smoke through the markets.

It started quietly.

Women whispered while selling palm oil.

They murmured while washing clothes by the river.

They spoke softly while tending farms.

The rumour was terrifying in its simplicity:

The British planned to tax women directly.

For the colonial government, it was administrative.

For the women, it was an attack.

Taxation meant control.

Counting meant ownership.

And ownership meant erasure.

Women were already working harder than anyone. They produced food, sustained trade, and held families together while men worked or migrated. To tax them was to reduce them to property.

And worse—no woman had been consulted.

Then came the moment that broke the silence.

In November 1929, in a town near Aba called Oloko, a colonial agent arrived. His job was to count people and livestock in preparation for new taxes. He approached a widow named Nwanyeruwa.

He asked her questions.

How many goats do you have?

How many children?

How much land?

Nwanyeruwa stared at him.

And then she asked a question that would ignite history:

“Was your mother counted?”

The argument escalated. Voices rose. Neighbours gathered. What should have been a routine colonial exercise turned into confrontation.

And when Nwanyeruwa walked away, she did not go home quietly.

She went to other women.

She told them what had happened.

And something ancient awakened.

The women understood immediately.

This was not about goats.

This was not about numbers.

This was about power.

The silence cracked.

And once silence breaks, it never returns the same.

— To be continued on 👉👉👉