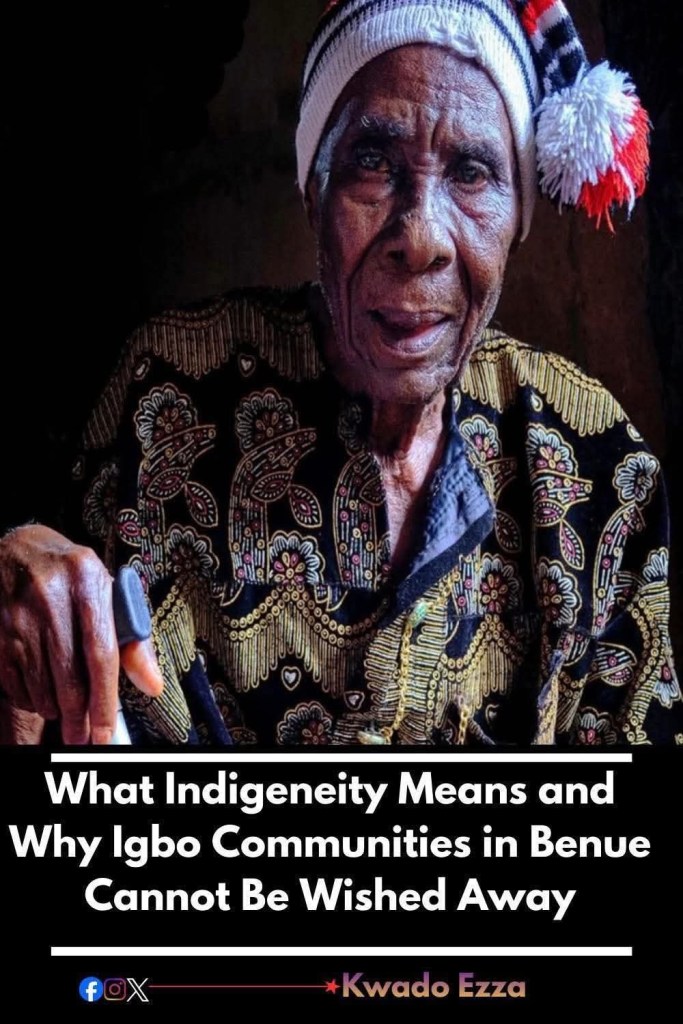

WHAT INDIGENEITY MEANS AND WHY IGBO COMMUNITIES IN BENUE CANNOT BE WISHED AWAY

~

WHAT INDIGENEITY MEANS AND WHY IGBO COMMUNITIES IN BENUE CANNOT BE WISHED AWAY ~ Kwado Ezza [23/01/2026]

In recent days, following my documentation of Igbo-speaking communities in Benue State especially in Ado and Oju Local Government Areas of Benue State, I’ve come to understand that many Nigerians genuinely do not know that there are indigenous Igbo people in Benue State. Some are surprised to hear that. Some are skeptical. Others see it outright, insisting that Igbo presence in Benue must be recent, politically manufactured or just an economic migration, with some saying they should go back to south east.

That reaction alone reveals how poorly we understand what the term “indigeneity” actually means in Nigeria, and how history has been distorted by colonial boundaries of state creation, administrative convenience, and postcolonial politics to incite division among peaceful communities that’ve coexisted for generations.

Indigeneity is not determined by present-day state boundaries or by the majority tribe that controls power today in contemporary political arrangements. Indigeneity is a historical condition that has to do with ancestral presence, continuous habitation, cultural continuity, and social integration or the people’s relationship with the land before modern state structures emerged.

Scholars explain that “Indigenous status is tied to a people’s historical continuity and cultural affinity with a region before modern administrative borders were created.”

According to the Federal Character Commission guidelines, someone can be considered an indigene of a place or local government area if:

- A parent or grandparent was an indigene of that locality, or

- The local government accepts the person as one of its indigenes.

Human Rights Watch and other analyses explain that “if a community can demonstrate ancestral presence, burial sites and continuity on a land, that community is indigenous by the understanding that Nigerians have traditionally used, regardless of the modern state boundaries.”

Given the above points, the Igbo communities in Benue are indigenous people of that land by every relevant historical, sociological, and legal definition in the Nigerian context because:

- They have existed there for a long time before colonial borders were drawn in 1914.

- They have deep ancestral and cultural ties to their settlements, bury their dead parents and do their ceremonial activities.

- Their presence predates Benue State’s creation in 1976. That is, they lived there for centuries before Benue State was created.

- Indigeneity is fundamentally about historical connection, and not by modern administrative units.

By that standard, Igbo communities in Benue State are not visitors. They are not guests or sojourners. They are not settlers who can be wished away at any time by ignorance. They are indigenous people, and legitimate members of the political and cultural community of Benue state.

Moving on, before the British amalgamated Nigeria in 1914, and before Benue State was created in 1976, Igbo-speaking communities have already existed across what are today known as Ado and Oju Local Government Areas of the state. These communities emerged through the same precolonial migration and ecological adaptation that shaped every other ethnic formations in the region.

In Ado Local Government Area alone, Igbo-speaking communities are found across districts such as Agila, Ulayi, Ijigbam, Ekile, Utonkon, and Igumale. Villages like Inikiri, Ojiegbe, Odoke, Amewulla, Osukputu, Ogburu Nkuta, Apa Ogbosu, Ichari, Onne, Azuigbelede, Okporicho, Amaeka, Aṅanchi, Ohinya, Odum, Azuoffia, Nwokporo Egbashi, Ikpadara, Ogebe, Ekpekere, Ohagelode, and many others are not accidental settlements. They are ancestral communities with their own internal histories, land boundaries, shrines, burial grounds, and leadership systems that predate colonial administrations.

In Oju Local Government Area, the Igbo presence is equally undeniable. Communities such as Ndiighe, Ekpuphu, Obokata, Idele, Umuoghara, Amaeka, Osidi, Edear, Ndu Nwankwo, Ekka, Idele Izzi, Usebe, Onyenu, Ogbala Izzi, Edele, and several others have existed for generations. These communities did not migrate into Benue in search of modern opportunities. They belong to the land historically and culturally. They did not appear because of elections. They did not settle temporarily and refuse to leave. They belong to the land in the same way every other indigenous groups in Benue belongs to theirs.

What complicates this truth is the colonial invention of state creation and boundaries. When the British imposed administrative borders for ease of control, taxation, and indirect rule, they paid little or no attention to ethnic landscapes that had evolved organically over centuries. Communities that had lived together for centuries before colonialism, suddenly found themselves classified under new political units thereby forcefully making some ethnic groups “minorities” in the new political entities.

Today, the consequences of that distortion are painfully visible. Despite their centuries of existence, the Igbo-speaking communities in Ado and Oju are still being neglected by the Benue state government. They see them as citizens only during elections and invisible after the election is won. They are counted only when their votes are needed and forgotten when development plan is shared.

In these communities, there are no motorable roads. During the rainy season, villages are cut off from each other as streams overflow and wooden bridges are collapsed or destroyed and taken away by flood. Pregnant women are carried on shoulders or wooden planks in search of healthcare miles away. Emergencies become death sentences not because they are severe, but because help cannot reach them

Electricity is absent. I didn’t mean unreliable or poor power supply, I mean “absent”. There are no poles. I didn’t mean either the poles fell or abandoned or that their transformers spoiled, I mean there has been no sign of electricity in the area since the existence of human beings on earth. No transformers, and not even any rural electrification plans. Children grow up without ever experiencing power supply. Businesses cannot function as there are no government market plans. Education remains stunted as there are no schools.

Water, which is regarded as the most basic necessity of life, is sourced from streams shared with animals. Both men, women, and children fetch water from the same points used by cows, goats, and dogs. This is not a metaphor, it is a daily reality. There is no sanitation infrastructure. No boreholes. No visible government intervention beyond election campaign seasons.

Yet, these communities are peaceful. They are not violent. They have not threatened the state. Instead, the youths organize themselves under community development unions to locally repair collapsed roads and revive wooden bridges using personal contributions.

The Igbo communities of Ado and Oju LGAs are indigenous to Benue State not because anyone permits them to be, but because their ancestors lived, farmed, worshipped, married, and were buried on that land many centuries before the modern Nigeria existed. That truth cannot be wished away.