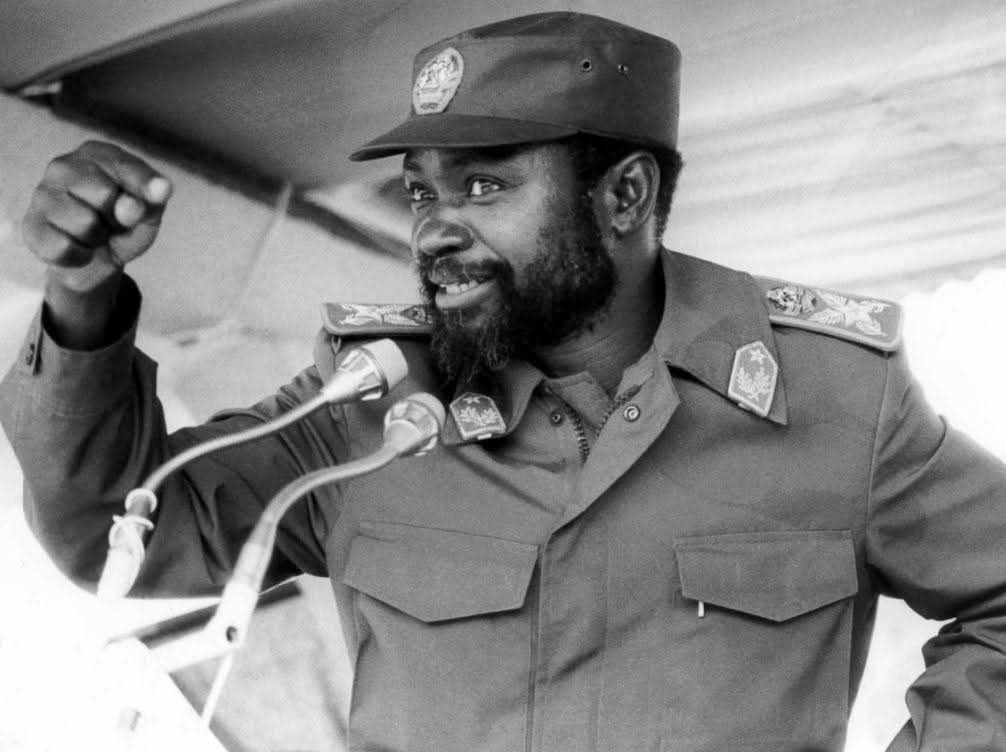

Samora Moisés Machel: Revolutionary, Ruler, and the Burden of Power

Samora Moisés Machel: Revolutionary, Ruler, and the Burden of Power

Samora Machel was not born into power; he was born into deprivation. Raised in 1933 in the rural village of Madragoa (now Chilembene) in southern Mozambique, Machel grew up under Portuguese colonial rule where African lives were cheap, labor was coerced, and dignity was rationed. His father, a farmer, lost land and cattle to colonial expropriation, a humiliation that would quietly shape Machel’s political consciousness long before he ever held a gun or a microphone.

Educated in Catholic mission schools and later trained as a nurse, Machel initially chose healing over violence but colonial racism ensured that even this path had a ceiling. African nurses were barred from advancement, paid less, and treated as inferiors in their own country.

That ceiling radicalized him.

By the early 1960s, Mozambique had become one of the fiercest battlegrounds of anti-colonial resistance in Africa. Machel joined FRELIMO (Front for the Liberation of Mozambique), a movement that merged nationalism, Marxist ideology, and armed struggle. After the assassination of FRELIMO’s founding leader Eduardo Mondlane in 1969, internal power struggles followed but Machel emerged not merely as a compromise candidate, but as a commanding presence. He was charismatic, disciplined, and ideologically rigid. In 1975, after Portugal’s Carnation Revolution collapsed the colonial regime back home, Mozambique gained independence, and Samora Machel became its first President.

Independence, however, is easier to declare than to govern.

Machel inherited a country deliberately left hollow by colonialism: no skilled workforce, no infrastructure designed for African development, and an economy engineered for extraction rather than sustainability. His response was revolutionary in ambition. He nationalized land, banks, schools, and healthcare. Education and healthcare were declared rights, not privileges. Illiteracy campaigns expanded rapidly, women were mobilized into political and economic life, and the language of dignity replaced the language of submission. For many Mozambicans, Samora was not just a president; he was the voice that finally spoke back to history.

Yet revolution has a darker twin: coercion.

Machel’s Marxist-Leninist vision demanded unity, discipline, and ideological conformity. Opposition real or perceived was treated as sabotage. Political pluralism was rejected. “Re-education camps” were established for those labeled reactionaries, criminals, or dissidents, blurring the line between justice and repression. Traditional authorities were sidelined, sometimes violently, in favor of revolutionary structures that did not always resonate with rural realities. The state spoke the language of liberation, but often governed through command.

Internationally, Machel placed Mozambique firmly in the socialist camp. He aligned with the Soviet Union, Cuba, East Germany, and other socialist states, receiving military and technical support. At the same time, he became a central figure in Southern Africa’s liberation politics. Mozambique under Machel openly supported liberation movements in Zimbabwe (ZANU), South Africa (ANC), and Namibia (SWAPO), offering bases, training, and political backing. This solidarity came at a brutal cost. Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa responded by funding and arming RENAMO, a rebel movement that plunged Mozambique into a devastating civil war.

By the early 1980s, the dream was bleeding.

The war destroyed infrastructure, displaced millions, and shattered the economy. Drought and famine compounded suffering. Faced with reality, Machel began to pivot quietly at first. He signed the Nkomati Accord with apartheid South Africa in 1984, agreeing to stop supporting the ANC in exchange for an end to South African support for RENAMO. Many saw this as pragmatism; others saw it as betrayal. It was, in truth, a confession: ideology could not feed a nation.

Then came the end.

In October 1986, Samora Machel died in a mysterious plane crash at Mbuzini, near the South African border. To this day, questions linger. Pilot error? Mechanical failure? Sabotage by apartheid South Africa? The truth remains contested, but the symbolism is clear: a revolutionary leader died not in triumph, but in exhaustion caught between vision and reality, principle and survival.

History did not end with him.

Perhaps one of the most striking postscript moments came years later, when his widow, Graça Machel, married Nelson Mandela in 1998. It was more than a personal union; it was a symbolic bridge between two liberation histories Mozambique and South Africa, armed struggle and reconciliation, revolution and negotiation. Graça Machel herself became a global advocate for women’s and children’s rights, carving an identity beyond both husbands, yet forever connected to the liberation era that shaped Southern Africa.

Samora Machel remains a paradox. A liberator who governed harshly. A visionary constrained by ideology. A nationalist trapped in global Cold War chess. He was neither saint nor tyrant in isolation he was a product of his time, and a warning to ours. Liberation without accountability risks becoming domination in new clothes. Power seized for the people must still answer to the people.

And perhaps that is his enduring lesson: revolution can break chains, but only humility can prevent new ones from being forged.